Show the code

summary(as.factor(SPECIES_CD_1))Data Handling Slides: Data handling in R pptx

In the following video you will learn how to import different types of files into your R work space. This skill will be integral for you to learn how to work with data in RStudio.

In R Markdown, if the summary of the categorical variables is not producing the same result as I shown in the video then try the following:

summary(as.factor(SPECIES_CD_1))Desktop version of R:

Keep your data in the same folder as this .Rmd file. If they are not kept in the same folder, then you have to tell R exactly where your data is by copying and pasting the file pathway directly into R. But overall, it is much easier and simpler to keep everything in the same folder. By default, the folder that your .Rmd file is in is called the “working directory”. This is the location that R assumes all of your input files are located. R will also place all of your outputs in this working directory, unless you specify otherwise.

RStudio online:

Upload the data file like demonstrated in the video, then write the same read.csv() function to import the data file onto R.

You can check what your working directory is by using the function getwd(), or “get working directory”. Interestingly, this code has no arguments - in other words, it does not need anything nested between the () to work - and its output should be a folder pathway to where your .Rmd file is. If you want to change your working directory - which at this point in time is not recommended - you can use the function setwd(), or “set working directory”. Unlike getwd(), you need to paste the desired folder pathway between the () of setwd() in quotation marks "" to set a new working directory. For example: setwd("C:\\Desktop\\Handling data in R\\") if you are using Windows and setwd("/Users/Desktop/Handling data in R/"). Finding a pathway in Mac is relatively complicated, so again, it is highly recommended that you place everything in one folder so you do not have to worry about setting a new working directory.

After setting a working directory, you can check all of the files that exist in your directory by using dir(). This function is fantastic for checking whether you are in the right folder, whether there are any extra files, and, most importantly, whether there are any missing files.

Checking whether you have all of the necessary files in your directory is important will make your life so much easier when you import data into R. For example, if the file trees_data.csv is in your working directory, all you need to do to import this into R is: read.csv("trees_data.csv", header = TRUE). If this file is not in your working directory, you would need to replace "trees_data.csv" with the entire pathway of the file - this will make your code much bulkier, more confusing, and less shareable.

Note also that the file name must be in "" and must be exactly like the file on your desktop. A common problem that students have is downloading the same csv file multiple times, resulting in an automatic “-1” (i.e. trees_data-1.csv) - in this case, you need to also add “-1” to your code for it to work. The argument header = TRUE is also important if you are importing data with existing headers (AKA column names). Try changing it to header = FALSE, what does the imported data look like now?

The functions for importing data from your hard drive into R are relatively intuitive: read.csv() for csv files, read.table() for txt files. There are other functions as well, but we will not be covering them in this course. These are the two main importing functions that we will use.

When installing packages, it is suggested that you # all install.packages() codes into comments because: * It will cause problems when you try to knit the .rmd file to Word and * it is generally insensitive to share this document to someone and make them accidentally install something into their hard drive

You can also export the data from R to txt or csv by using write.table(). This table, by default, will be exported to your working directory. Try typing ?write.table into the console, you can read more information about this function there!

# Location of the parent directory / folder you saved this .RMD file

getwd()

# Listing all files in the directory

dir()

# Importing a csv file

tree1 <- read.csv("trees_data.csv", header = TRUE)

# Importing a .txt file

HDB <- read.table("height_dbh.txt", header = TRUE)

# Importing VRI data

vri_data <- read.csv("VRI_data.csv", header = TRUE)

# Importing an excel data file

#install.packages("readxl")

#library("readxl")

#tree2 <- read_excel("trees_data.xlsx")

# Export data as a .txt file

write.table(HDB, "MyData.txt")

# Export data as a .csv file

write.table(HDB, file = "f1.csv", sep = ",", col.names = NA, qmethod = "double")Recall that there are several ways that you can call for a variable in a dataset: (1) using $ or (2) using attach(). attach(), you guessed it, attaches the data to this R session so we do not need to use $. attach() is usually more useful when you are only working with 1 dataset in your .Rmd file, else it will get very confusing if you or someone you share this file to run this file out of order.

We can find a summary of all statistics of a dataset using summary(). In the example code below (vri_summary = summary(vri_data)), you may see that we are using a = instead of a <- to assign a value to a variable. In this case, = and <- function similarly (you can change = to <- and re-run the code). However, they may have different functions in other scenarios. We will not be covering these scenarios, so for the context of this course, just understand that = and <- are similar. Important note: Recall that R’s “equal to” is actually ==. So = and == are VERY different!

You can also find the dimension of the data using dim(). This should tell you how large the dataset is (AKA numbers of rows and columns) without you having to run the actual data. This may save you some time if your dataset is too big.

Finally, head() and tail() print the first and last few rows of a dataset for you - again, helpful if your dataset is very large. You can also specify how many rows you want to print by adding an integer after the data frame name. For example, head(vri_data, 10) will print the first 10 rows for you.

attach(vri_data)

# Set an object for string the data summary

vri_summary = summary(vri_data)

# Dimension of the data

dim(vri_data)

# Print first few rows

head(vri_data)

# Print last few rows

tail(vri_data)Once we have successfully imported our data into R and gained general information about it, we can also go into more specific data exploration. Firstly, we can tell R to only extract a few specific rows and columns from the dataset by using []. Note that the first argument in this bracket represents the rows and the second argument represents the column. For example, when we type vri_data[100:110, 4:5], we’re telling R to extra rows 100 to 110 and columns 4 to 5. We use : between two numbers to indicate that it is a range of sequential numbers that we want. So, 100:110 means from 100 to 110.

If it is not a range of rows/columns that you want to extract, but very specific, non-consecutive rows/columns, you can nest all the rows/columns that you want in a vector, like in vri_data[c(10, 20, 23), ]. Here, we only want rows 10, 20, and 23. Finally, if you want to extract all rows or all columns, simply leave the argument blank. In other words, vri_data[10, ] tells R to extract row 10 and all columns, but vri_data[ , 10] tells R to extra all rows and column 10.

The rest of the functions in this tutorial have already been covered by a previous R lecture file or your assignment. The functions themselves are not hard, it is understanding what they do and when to use them that requires a bit more thought. And as always, the best way for you to be better in R is to practice!

# Extracting some rows and all columns

vri_data[10:13, ]

# Printing all variable names

names(vri_data)

# An example of creating a variable with sequential values

x <- 1:5

# Finding the average of the variable x

mean(x)

# Printing the average of variable ProJ_Age_1

mean(PROJ_AGE_1)

# Printing data types of some variables

class(SPECIES_CD_1)

class(PROJ_AGE_1)

class(PROJ_HEIGHT_1)

# Summarizing the entire dataset

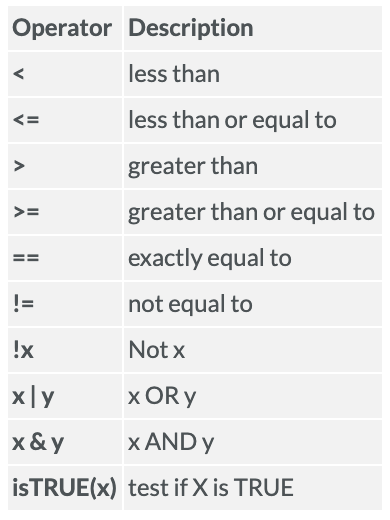

summary(vri_data)The arguments that use logical operators give us outputs of True or False.

In the context of this course, logical operators are most useful in conjunction with the function subset(). You will see an example of subset() in the second code chunk in this file - heads up, this function will play an important part of your next assignment on Graphical Presentation on R. Again, note the difference between = and ==.

You can use logical operators to do a variety of things. For example, when we assign y <- c("a", "bc", "def"), we can check which components of this vector is equal to “a” by writing y == "a". When you run y == "a", the output should be TRUE FALSE FALSE. This is because R is comparing all components of the vector y to “a”. Only the first component of the vector is “a”, so only the first comparison of the output is TRUE. There are so many other things that you can compare. For example, you can also check whether the lengths of two vectors are the same, or if one is longer than the other: length(y) == length(x) or length(y) > length(x). Again, the output for these codes should only be TRUE or FALSE.

# character vectors

y <- c("a", "bc", "def")

length(y)

#> [1] 3

nchar(y)

#> [1] 1 2 3

y == "a"

#> [1] TRUE FALSE FALSE

y == "b"

#> [1] FALSE FALSE FALSE

# Logical Operators

x <- c(3, 7, 1, 2)

x > 2

#> [1] TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE

x == 2

#> [1] FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE

!(x < 3) # x not equal to less than 3

#> [1] TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE

which(x > 2)

#> [1] 1 2Recall how we import data into R using read.csv() and the csv file that we are importing needs to be in the same folder as our Rmd file, in other words, our working directory. Below is also an example of a code that we would use to direct R to a file that does not reside in our working directory - we need a copy and paste the whole pathway into R.

After importing a dataset into R, we can actually also change the type of data of the dataset’s variables. For example, we can convert a variable from numeric to factor using as.factor(). In the converting to a factor subsection below, as.factor() is hashtagged into a comment because if you check the class of SPECIES_CD_1, it is actually already a factor, so we do not have to convert it to a factor. Another reason is that, as.factor() works almost identical to factor(). The main difference is that factor() is newer and slightly more preferred.

So what exactly is a factor? In simplest words, a factor takes categorical (discrete) variables and store them in what we call levels. For example, in factor(c(1,0,1,0,0,0)), the levels are 1 and 0. We can now use these levels to turn them into labels, like what we did in factor(c(1,0,1,0,0,0), levels = c(0, 1), labels = c("boy", "girl")) where we changed all 0 values to “boy” and all 1 values to “girl”. More information on what factors are can be found here.

You can also check the class and mode of our new object after we have identified it as a factor. Note that mode() here does NOT code for the mode (AKA most common) value, it tells us the storage mode of an object. Again, more information on mode() can be found in the help tab in the bottom right corner of RStudio.

As you have been frontloaded before, in this course, logical operators are most useful when nested in a subset() function. The examples below show you how to do that. There are also extra notes/comments of common mistakes and how to troubleshoot them in the code chunk below. Something important to note is that when you’re using logical operators, each logical statement needs to include three things: (1) verse A on the left side of the statement, (2) a logical operator, and (3) verse B on the right side of the statement.

A common mistake that student makes is forgetting the first requirement when nesting several logical statements into one subset(). For example, subset(vri_data, SPECIES_CD_1 == "PLC" | SPECIES_CD_1 == "SS") is correct, but subset(vri_data, SPECIES_CD_1 == "PLC" | "SS") is NOT. You can also store subsets the same way that we store any other objects.

# Importing VRI data

vri_data <- read.csv("VRI_data.csv", header = TRUE)

#vri_data <- read.csv(file="C:/Users/suborna/VRI_data.csv", header = T)

#attach the data

attach(vri_data)

# converting to a factor

class(SPECIES_CD_1)

#as.factor(SPECIES_CD_1)

summary(SPECIES_CD_1)

levels(SPECIES_CD_1)

# Example

kids <- factor(c(1,0,1,0,0,0), levels = c(0, 1), labels = c("boy", "girl"))

kids

class(kids)

mode(kids)

# subset of data

plc_stands <- subset(vri_data, SPECIES_CD_1 == "PLC" )

sub_vri <- subset(vri_data, SPECIES_CD_1 == "PLC" & PROJ_AGE_1 > 100)

dim(sub_vri)Tree height text fileheight_dbh.txt

Tree data csvtrees_data.csv

Tree data workbooktrees_data.xlsx

VRI data csvVRI_data.csv

Logical vectors belong to the logical class. The elements of a logical vector can be TRUE, FALSE, and NA (for “not available”). You generate logical vectors by conditions. You can use logical operators to test conditions (<, <=, >, >=, ==, and != for inequality). If you have two logical expressions A and B, you can get their intersection (A & B), their union (A | B), and their negation !A.

Besides numeric and logical vectors, there are character vectors that contain text. Remember that you enter character values by enclosing them in either double (“) or single (’) quotes. The paste() function is sometimes useful when working with character vectors. It allows you to link vectors into character strings. Type ?paste into the RStudio Console pane and hit Enter to find out more about the past() function.

The simplest thing to use R for is as an interactive calculator as demonstrated in part 3 of this module. This is kind of nice, but really, we wanted to use the programming language R instead of a calculator to automate processes and to avoid repetition. If you want to use the result from one calculation in a second calculation, you have to create a variable that stores the result of the calculation. You assign a value to a variable by using the assignment operator <-. I already talked about the arithmetic operators (+, -, *, /, and ^ ). Some functions of interest in addition to log(), exp(), and sqrt() are as follows:

When you perform calculations with vectors, you have to be careful about what happens when the vectors are not the same length. If you use vectors of different lengths, R will ‘recycle’ the shorter vector and replicate it as many times as need to match the length of the longer vector. This works well if the longer vector is a multiple of the shorter vector. However, when that is not the case, R will produce a warning.

The easiest way to generate a sequence is with the colon operator :, for example, 1:3 codes for a sequence of 1 to 3. However, if you want some more control about what the sequence is supposed to look like, you should use the seq() function, with its arguments ‘from,’ ‘to,’ and ‘by,’ which define the start-point, end-point, and interval of the sequence. If you want to create a vector of a specific length that contains a sequence, you can use the argument ‘length’ instead of ‘by’ to define the length of the vector.

We have only entered data into R by hand by creating different types of small vectors. What do we do when we want to process large amounts of data? We need to be able to read input for our analyses directly from files and sometimes it is also useful to write output to a file for further analysis. R provides the infrastructure to both import and export data. We have covered how to read data from files and write data to files in RStudio in the video. Creating graphs is another form of output - we will cover graphs in the next R module.

You can find around 100 datasets supplied in R. To see the list of available datasets type data() into the Console Pane. We will use these data sets to practice exporting and importing data. You can also use these datasets to practice for your midterm and final. The fifth data set in the list is called CO2. Let’s look at it. Type ?CO2. The help page for the data set will open up. It contains information about how the data were collected and what variables the dataset contains. You can print the first 6 observations into the Console Pane using head(CO2). I like doing that to see what the dataset looks like being analyzing or manipulating it. You can print the names of the data set into the Console Pane using names(CO2). dim(CO2) gives you the dimensions of the data set: 84 observations and 5 variables. Check out these functions in the R help window: head(), names(), dim().

Most often, we deal with space-delimited .dat or .txt files, tab-delimited .txt files, or comma-separated values files (.csv). You can read and write any of these data types with the read.table() and write.table() functions, respectively. For .csv files, R has read.csv() and write.csv() as additional options. In the built-in R help, you can find a lot of details about these functions and what arguments they contain.

In R Markdown, you can keep the Rmd file and the data files on the same folder, this way you only need to write the name of the data in any of the read functions above to import the data. On RStudio Cloud, you only need to upload them and call them in your program.